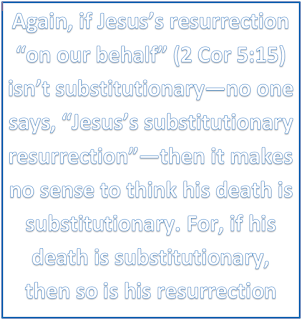

In response to some social media responses and discussion to these posts on (mainly) Facebook, I asked Andrew to write up some thoughts. There are those who think Andrew is "throwing the baby out with the bathwater", and the reason given is something like "because Paul articulates the saving significance of Jesus's death in substitutionary terms earlier in Romans / elsewhere". However, as no texts have yet been referenced by these interlocutors it is difficult for Andrew to respond. Andrew adds that, especially given the 6th post in this series ("Substitutionary Resurrection?"), the onus is arguably now on folks who think there's some "substitutionary" magic bullet—to provide this evidence. Either way, the point of Andrew's posts was to tackle Mike Bird's top three texts, which is really how this mini series of arguments needs to be adjudicated. And we are looking forward to Mike's video response in due time, which I will of course repost here!

But one question, raised by an old University friend of mine, Matthew, deserves a little more discussion, and Andrew, it turns out, had something prepared. So this post will first talk about this proposed correction of Andrew's case before wrapping things up with a conclusion.

In a—I promise—final post, I will provide a link to an important PSA critique from a trinitarian angle and add one other set of concerns about the word "penal".

*Hands the microphone back to Andrew Rillera*

Passover

Some have asked about substitution in 1 Cor 5:7 because there Paul says clearly that Jesus is our paschal lamb (pascha). A few things need to be kept in mind here.

|

| Image from https://www.templesolel.com/ |

For one, as I said in Part 1: Many people are unaware that not all Levitical sacrifices have a

kippēr function. The “peace” or “well-being” sacrifices (Lev 3, 7:11–21) do not have an atoning function. Conveniently, it’s pretty easy to know if a sacrifice is atoning or non-atoning: if the laity

eat from it, then it cannot be an atoning sacrifice. E.g., we know that the Passover is type of corporate thanksgiving well-being sacrifice because it is

eaten by the laity (and has unleavened bread and a one-day expiration date (compare Exod 12 with Lev 7:12, 15).

There are three types of non-atoning sacrifices, lumped into a single broader category called the “well-being” sacrifices (šĕlāmîm). What unites these three are two significant facts. (1) These are the only sacrifices that the offerer eats. And (2) these are all non-atoning sacrifices. If a sacrifice has an atoning function, then the offerer cannot eat from it.

Significantly, while the well-being sacrifices could be offered by individuals whenever they felt like it, there are two important corporate well-being sacrifices: the Passover and the covenant inauguration/renewal (cf. Exod 24:5, 11; Deut 27:7; 2 Chron 15:10–12; 29:31, 35; 30:22–24; 33:16). Paul undeniably associates Jesus with both of these non-atoning sacrifices in 1 Corinthians (Passover in 5:7 and covenant inauguration in 11:25).

What is important for our purposes is that right off the bat we need to exclude 1 Cor 5:7 as talking about “atonement” (kipper) because the Passover is not an atoning sacrifice by definition. But once that is out of the way, what about the notion of “substitution” in general?

If one was inclined to say that it substituted for the firstborn in each household since failure to paint blood on the doorpost would result in the death of the firstborn, then one would also have to say that leaven is substitutionary as well since failure to comply with removing it and not eating it would result in that person’s death also (Exod 12:15, 19). In other words, just because something averts being cut off does not mean it is “substitutionary.” Hypothetically, if the Hebrew family ate a lamb but didn’t remove the leaven the firstborn along with the entire family would perish. So the lamb was not really “substituting” for the firstborn otherwise that would be sufficient to automagically have spared him. The consequences for not partaking of the Passover properly cannot be reduced to a logic of an isolated discrete instance of the lamb substituting for the firstborn. The feast needs to be understood as a whole.

Moreover, the Torah already tells us who the substitute for Israel’s firstborns are: The Levites (Num 8). It was not as if the firstborn of every household was threatened every year with death unless as substitute was offered in its place on Passover. The firstborn aspect of the first Passover was dealt with in Exod 13 immediately after the instructions in Exod 12. Here the firstborn aspect takes the form of redemption, which eventually gets taken up in Numbers 8 with the dedication of the Levites for tabernacle service in place of the firstborns. So the firstborn aspect of the first Passover is literally never part of any subsequent Passovers. To all of a sudden think Paul calling Jesus the Passover in 1 Cor 5:7 is him talking about Jesus as a substitute for all humanity (so I guess “firstborn” has now lost all meaning if it applies to…everyone??) strains credulity.

In any case, the point of the Passover celebration was upon preservation, deliverance, and formation into a covenant people, not some substitutionary moment of atonement. To conceptualize the Passover with substitution would be to miss the entire narrative thrust of both the historical moment and its continued remembrance in celebration each year afterwards, especially after the exile. In its first instance, the Passover lamb was a protective shield of sorts in order to preserve the whole people of Israel for their coming liberation from Egyptian slavery (12:13, 23–27, 31–32, 42, 51). Afterwards, it was the cultic marker of the preservation of Israel in order for them to be made into a kingdom of priests (12:14, 17, 24–27, 42; cf. Exod 19:4–6).

When Paul refers to Jesus as the Passover sacrifice in 1 Cor 5:7 it is pretty easy to rule out that he is conceptualizing this has a substitution that otherwise should have been the Corinthians’ deaths. The point in this passage is about the necessity for the community to be pure (eilikrineia) and true (alētheia) (5:8); free from immorality and every kind of wickedness (5:1, 8–11). This is why they should “remove the wicked person from among [themselves]” (5:13)—the person sleeping with his step-mother (5:1).

If Paul thought of Jesus as a substitute for people’s sins, then the solution would be to reiterate that nothing ought to happen to this sinner because Jesus’s took his punishment instead of him. But this is exactly not what Paul writes. Indeed, Paul’s instructions to expel this immoral person are for the purpose of destroying this person’s flesh (5:5a). True, this has the further purpose of saving his spirit (5:5b), but importantly, it is the destruction of his flesh that leads to the salvation of his spirit not, as we would expect with a substitutionary understanding of Jesus’s death, the destruction of Jesus’s flesh in his place.

Crucially, Paul brings in Jesus only in order to justify why the community ought to

expel this sinner from among them. That is, conceptualizing Jesus’s death as a Passover sacrifice serves Paul’s point of the need to excommunicate the immoral person. The rhetorical move is anything but talking about Jesus as the substitute for an immoral person.

Just like the Passover celebrated the preservation, deliverance, and formation of Israel into a covenant people, Paul says that Christ’s death signals their deliverance (from every kind of immorality and wickedness in its immediate context) and formation as an unleavened community that is pure and true.

Paul’s logic here runs this way: since Jesus is our Passover, then we have an obligation to “celebrate” this fact by removing all leaven, which Paul midrashically interprets as immorality and wickedness, from our community that has been brought into existence by this Passover and therefore, we need to remove this immoral person. The point, then, about using the image of Passover is to say that Jesus has delivered and formed a pure community, therefore we are under obligation to keep it pure and free from immorality. There is nothing substitutionary going on.

No matter which way one slices it, Paul is not operating with a notion of substitution in either 5:7 or 11:25. In between these passages in 1 Cor, Paul asks, “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing [koinōnia] in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a sharing [koinōnia] in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake [metechō] of the one bread. Consider the people of Israel; are not those who eat the sacrifices partners [koinōnia] in the altar?” (1 Cor 10:16–18).

Here we get a clear statement that Paul is working within the logic of the non-atoning well-being sacrifices, of which Passover is a special corporate instance. First, this cannot be about substitution by definition, because it is all about “sharing” (koinonia) (1 Cor 10:16, 18, 20) and “partaking” (metechō) (10:17, 21) in the offering and thereby having fellowship with God (see part 5 for the definition used). Second, not only is it explicitly and undoubtedly about “participation,” but this also means Paul cannot be conceptualizing Jesus’s death as an “atoning” (kipper) sacrifice since these cannot be eaten by the offerer. And if there was any doubt about this, he actually quotes from Exod 32:6 earlier in 1 Cor 10:7, which is about the Israelites eating well-being sacrifices before the Golden Calf, whom they call YHWH, the LORD.

According to Paul, it is by partaking of the well-being offering that is Jesus’s body that we become made participants in his broken body and shed blood and made members of the new covenant (1 Cor 10:16–18; 11:23–25). It is by this that we become, “living sacrifices” “living well-being” sacrifices ourselves (cf. Rom 12:1). This is why Paul calls himself a drink offering, which accompanied the well–being sacrificial feast (Phil 2:17). And he says the Philippians’s gift can be thought of the smoke of the well-being sacrifices that pleases God (4:18).

So I think the well-being sacrifices are the key to understanding the way Paul conceives of the relationship between Jesus and the Church, which Paul calls Jesus’s body (1 Cor 12). The well-being sacrifices allow Paul a way to make sense of a believer’s very real participation and union with Jesus’s death (and resurrection) because these are the only sacrifices the offerer has a share in themselves. So it makes perfect sense that well-being sacrifices are used to make sense of Jesus’s death for a movement that saw itself as the Body of the Crucified Lord and called to share in his sufferings as well. If Jesus is a well-being sacrifice and we are his body and we sacrificially partake of his body and blood, then this means we become a collective “living well-being sacrifice” as a new covenant people united to the final Passover lamb.

Conclusion (Again)

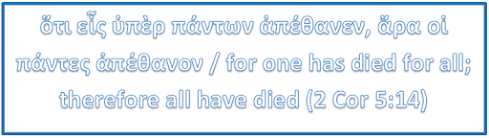

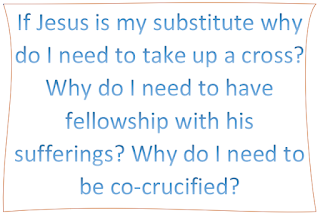

Paul’s basic narrative logic of salvation seems to be this: (1) Disobedience/sin is ubiquitous in human beings. (2) This causes all sorts of problems for humanity and the biggest problem is that all this sin/disobedience results in death. (3) Jesus was truly human in every way and fully obedient, died, and was resurrected from the dead. (4) The resurrection means Jesus has defeated death. (5) Therefore, if Jesus defeated the ultimate result of sin/disobedience, then he in fact defeated sin/disobedience itself. (6) Therefore, if one is united with Jesus’s death (co-crucifixion), then one can walk in the newness of life—a life of obedience like his—and be assured of one’s own resurrection as well. Everything Paul says on the topic of salvation either illustrates, explicates in further detail, or provides the warrants for these points.

The remedy for Sin/sins according to Paul is deliverance and rescue. And this is because Paul conceptualizes Sin as a personified power and agent that deceives, enslaves, and kills, which leads people to commit sins, and so Sin needs to be conquered, subdued, and condemned. Sin for Paul is not conceptualized as a contamination that needs to be disinfected from holy objects through cultic atonement. Other NT authors such as 1 John and Hebrews go this route, but there is no evidence Paul himself does. Paul is using another conceptual framework than kipper and this framework is explicitly about union and participation.

At no point would substitution (penal or otherwise) properly conceptualize what Paul thinks is going on. If we are determined to pick a word to conceptualize Paul’s thought, then Irenaeus’s use of the Pauline word “recapitulation” would be it (see

anakephalaioō in Eph 1:10). This whole thing is not “place taking” (substitution), but rather “place sharing” (solidarity, union, participation): The Son of God first shared and participated in the cursed condition of humanity albeit fully obedient (incarnation), delivered it from that condition (resurrection), and then and only then can anyone now share and participate in his divine condition (justification, sanctification) since he is the new “head” of humanity.

Labels: Rillera